By Jason Barney, Principal

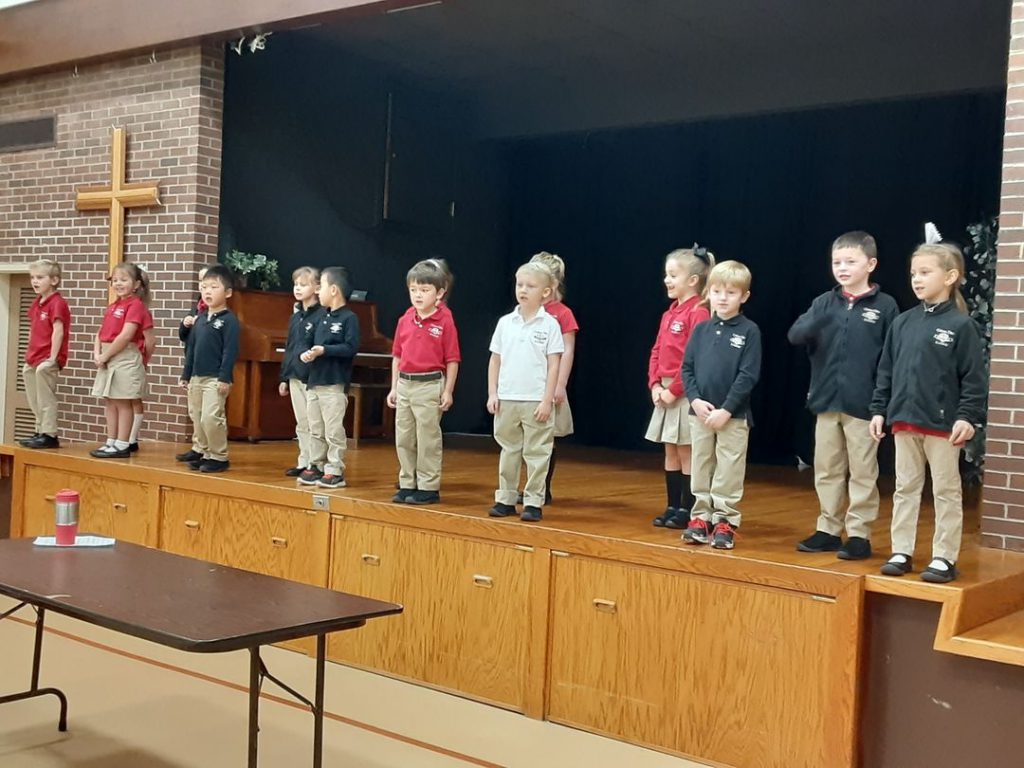

If you are a parent or student in the Coram Deo community, you are no doubt aware of some changes at school from previous years. One of those changes is the use of narration as a learning exercise in the classroom.

Socratic discussions, guided questioning, the inspirational or informational lecture, writing prompts, recitations and student speeches—these traditional methods are all part of the warp and woof of education at a classical school. And each of these is transformational in its own right.

Socratic discussions foster deep thinking. Questioning solidifies detailed knowledge. Lectures provide perspective. Recitations store up the heart with true, good and beautiful words. Essays and speeches develop students’ judgment and expression.

But one missing ingredient in many classical schools today is the fundamental power of telling. Narration is the process of learning by telling from what you have read, heard or seen. And as Charlotte Mason, a Christian British educator of the late Victorian era, said,

“Whatever a child can tell, that we may be sure he knows. And what he cannot tell, he does not know.”

In this CDA article, I want to share with you a taste of what I’ve learned about the power of narration, and in so doing, give you a glimpse into the simple but transformative experience of a CDA student. Narration works through the classical principle of imitation and operates according to the findings of modern brain science.

Narration and Brain Science

One the surprising factors about classical education to many parents is the support that classical methods receive from brain science or cognitive psychology. The classical methods of instruction I mentioned above are not being superseded by the insights of modern neuroscience; instead, they are being reaffirmed.

(It is really modern ideology and education fads that are getting in the way of student learning, but that is a whole other topic….) Narration was the first Greek progymnasmata or preliminary exercise for rhetorical training that we have record of (in the work of Aelius Theon, a rhetorical teacher in Alexandria in the 1st century A.D.). But narration also is supported by modern research on retrieval practice.

Studies show that true and lasting learning occurs in our brains when we do the hard work of retrieving information from memory. It’s actually in the process of trying to remember something in detail that we signal to our neurological system that a memory should be stored for the long term.

Think about the brain’s memory system as a desk. You can only put a few things on top of the desk ready and accessible, but then there is a drawer just below the desk, where you might temporarily store things (short term memory) before discarding them or filing them in a filing cabinet for long term storage (long term memory). When you try to recall something from memory, it’s like you’re taking something out of the desk drawer to file it in a place where you can easily access it again.

In order for that to happen, you have to have already had something on top of mind by focusing on it (top of desk), and let it pass from your focus momentarily (put in your desk drawer), before picking it up again to file it. What we call learning, then, actually occurs not when we put something on top of the desk, but when we are filing it away by retrieving it from the short term memory. (I owe this desk analogy to Dr. Daniel Levitin’s The Organized Mind, a book I highly recommend.)

What’s actually occurring in our brains is that electrical signals are firing through a set of millions of neurons simultaneously. And as Hebb’s law states, neurons that fire together wire together. When a memory is recalled, the neural circuitry is fired together again, and a fatty sheath (myelin) is wrapped around that network, as a sort of insulation to make it easily accessible again.

Narration is an ideal way to engage in retrieval practice, because students are asked to tell back in detail something they’ve just put in their short term memory. Narrating makes the learning process more efficient by taking time to file information into long term memory right away. Otherwise, more information is lost in the wastebasket of the mind during the brain’s normal process of clean-up.

Narration as Imitation

But learning by telling is only as good as the content that students are focusing on. This is where the classical principle of imitation comes in. Narration works best when students are telling about things that are good, true and beautiful. The curriculum matters.

That’s because, as with recitation (memorizing poetry, passages of scripture or historical speeches), students are storing their minds with whatever they narrate. So classical Christian schools care about the quality of what is narrated. We want students to think about “whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise” (Phil 4:8 ESV).

In classical Christian education, students are to imitate the masters, the great books, the great works of art and music, the great discoveries of scientists, inventors and mathematicians. But narrating rich texts and stories is only not best for students’ development, it’s enjoyable and inspiring!

This principle of imitation means that often the curriculum written by a standard modern textbook committee won’t be as ideal as one written by a single expert with a vital grasp of the topic. Style matters, as well as substance. Narrating should engage students’ hearts, as well as their minds.

One of the more powerful features of narration is how natural it is for us to imitate rich content. It’s as if our minds were primed to grow and reproduce, to imagine and think thoughts after the pattern of a great thinker. Perhaps this is an aspect of our human nature, that we would reflect the image of our Story-telling God and learn by telling.

If you’re an educator or interested in learning more, you can find out more by reading Mr. Barney’s book A Classical Guide to Narration published by the CiRCE Institute.

RSVP for an Open House